As I sat in Ms. Arnstein’s classroom, surrounded by literary paraphernalia, I could vividly imagine the scene that she was depicting to me. About a week before I had met with her for our interview, Ms. Arnstein had planted the seeds for her garden in small containers at home—holding up her fingers to approximate the size and depth—under the grow lights in her basement, where she had allocated a special space, specifically for that purpose. Her seedlings even had special heat mats. She had ordered her seeds from a seed catalog around President’s Day — for her, the first beckoning of spring even before the snow melts. Ms. Arnstein then explained how, after the seeds sprouted, she would transfer the seedlings to larger pots and eventually introduce them outside in the weeks leading up to Memorial Day in a process called “hardening.” Her enthusiasm was radiant and somewhat contagious; I kept smiling throughout our whole interview.

When I had walked into her classroom that day, I really had no idea of the extent of Ms. Arnstein’s gardening. Some Juniors had offhandedly mentioned that she talks about her garden “a lot,” but this didn’t do justice to the eagerness with which she avidly described the process. My family and I have a small herb garden, with a handful of tomato plants and maybe a pepper or two, but Ms. Arnstein’s covers a significant section of her backyard, as she showed me in her pictures. As she flipped through pictures on her computer, she had to pause and think about how many garden beds she had. “Four were already there when we moved in,” she said, “but now we have nine, as well as the pumpkin patch and the raspberries.”

The house’s previous owner had a beautiful flower garden, she explained. Her family’s move was what had really sparked the beginnings of her larger-scale agricultural pursuits; before then, she and her husband had participated in a community garden. With just under half an acre of property in the new house, however, they were able to expand—and incredibly so. Throughout our interview, Ms. Arnstein kept recalling different vegetables that she had forgotten about when I’d asked about her garden initially: bok choy, escarole (a leafy green somewhat similar to kale and lettuce, but related to endives), tomatoes, potatoes, kale, squash, carrots, black beans… the list goes on. She even grows pumpkins, which grow huge in a small section she pointed out to me in the back of the picture. But, she noted, the apples, are a finicky endeavor that have yet to be brought to fruition. Last year, they planted brussels sprouts for the first time, but the sprouts ended up tiny, since they were too close together. It’s a running joke, now, with her husband. Although, I remember her declaring, “No zucchini!” with a laugh. Apparently they grew too big, and you didn’t know what to do with all of them. I’m really not sure how many vegetables it’s even possible to grow in Minnesota’s unforgiving climate, but some part of me suspects that Ms. Arnstein has at least tried to grow most of them.

In her own words, gardening is a learning experience. Upon my inquiry, Ms. Arnstein recalled that most of her knowledge came from years of experimentation by trial-and-error. Others at the community garden aided her and her husband, as well, as does a friendly neighbor today. In the first year in their new house they started with tomatoes and basil. She and her husband then expanded their garden beds and started growing their harvest from seed. I supposed that such a switch would have been hard, but Ms. Arnstein just shook her head and admitted that the switch actually went smoothly. Now, her own family and friends ask her to start seedlings for them.

The joy is in the whole process, from starting the seedlings to reaping the harvest and cooking. “You get to nurture new life; watch it grow,” Ms. Arnstein said. Sometimes it goes well, and sometimes—perhaps harkening back to the miniature brussels sprouts or the zucchini—it doesn’t. And that’s okay; gardening is a continually evolving process; every season has different weather, perhaps different plants. Ms. Arnstein notes her observations of what went well and what did not, and she keeps a gardening journal with grid maps of her garden’s layout and produce. Every year is a new chance to experiment. The end result notwithstanding, the process itself has a lot to teach anyone.

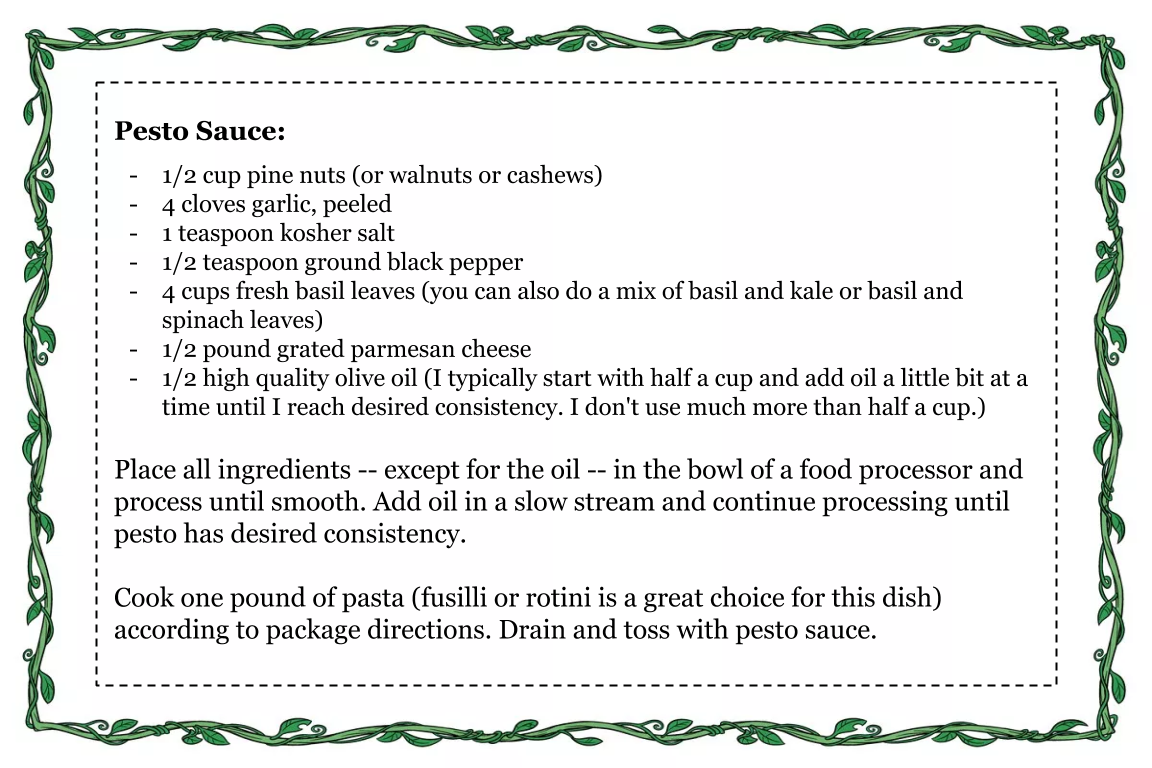

It almost seemed redundant to bring up the benefits of gardening; I could clearly see Ms. Arnstein’s passion for it. Besides the obvious benefit of fresh, delicious fruits and vegetables and the joy of knowing that winter is almost over, she reflected that growing her own food taught her how to cook with whole ingredients. Ms. Arnstein admitted that she actually prefers reading cookbooks to gardening books. She simmers tomatoes and cans them, and her family has pesto throughout the year since she freezes it. Ms. Arnstein said that you can really add anything into a pesto.

So how does one start a garden? Obviously you don’t have to have nine beds and ten different crops in your first year, but you can start with a few tomato plants, maybe some herbs. Basil and cilantro are easy and fairly versatile. You’ll need a huge pot, bigger than you might think, for the tomato plant, as well as a cage to support it as it grows. Even a large hardware store bucket would probably do. A long, thin planter is good for lettuce as well. And then, you’ll need to either plant seeds, which isn’t actually too difficult, or buy seedlings. Ms. Arnstein recommended going to a local farmer’s market. Talk to people, look for vendors who seem knowledgeable and whose plants seem healthy. And then, you’ll need to plant them (weather permitting, of course). Like a chef will alter the recipe for a certain dish, the “recipe” for a garden varies depending on what the gardener wants. I was already coming up with ideas for my own garden this season.

“Gardening is so delightful,” said Ms. Arnstein, “a great summer-oriented activity.” Unlike other summer pleasures, though, this one sticks around longer than a melting popsicle. The experience of growing your own produce, from farm to table, will surely alter the way you think about food.