“I have been known to fence with a quill.”

— Amor Towles

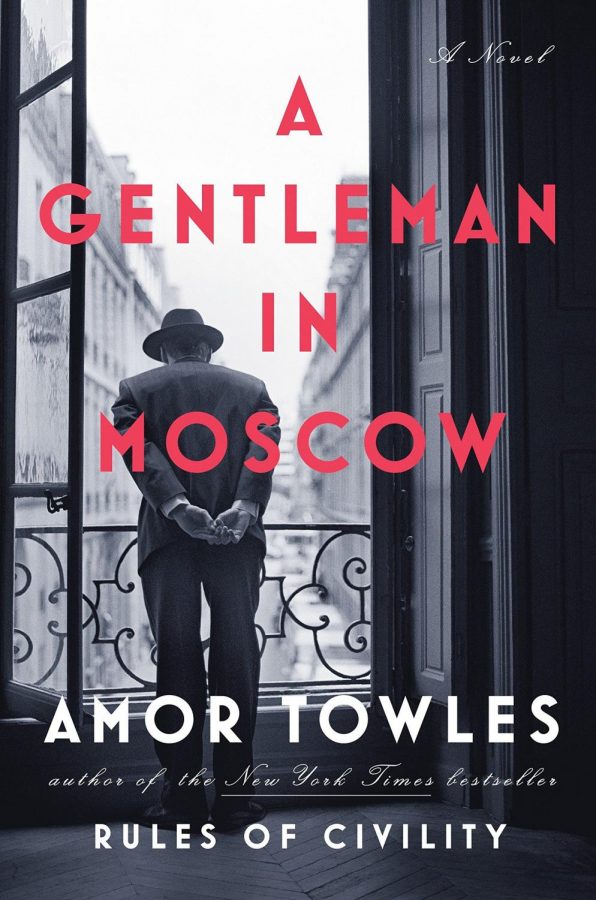

Amor Towles’ novel, A Gentleman in Moscow, opens with a map drawing of Moscow, Russia, in the year 1922. An inset map focuses on the Theatre Square, a small area encompassing a few city blocks, and notable buildings such as the Bolshoi Ballet and the Metropol Hotel, where the entire story takes place. Count Alexander Rostov is sentenced to house arrest in the hotel, ironically rendering the map useless in a way; in studying the map, the reader learns about a world that the protagonist himself cannot access. However, despite the limiting quarters of the hotel’s walls, the Count’s world (and the reader’s) expands with Towles’ brilliant writing. The Metropol Hotel becomes his entire universe. The patrons, the staff, and the events come to life easily within the pages of the novel, and each description of the hotel’s assorted occupants, each unfolding of the plot, each precise action the Count takes unfolds with stunning clarity.

The plot begins simply. In 1922, the Count Alexander Rostov, a 33-year old Russian aristocrat, is sentenced to house arrest at the Metropol Hotel in Moscow. Earlier, during the Russian Revolution, the Count had penned a poem of “a call to action,” which offset the crime of his noble status and rendered his punishment less severe—imprisonment, as opposed to execution. The novel, however, does not have a strong central plot, mainly focusing on the extraordinary life of the Count. Perhaps the narrowing of his world allows all within it to come into focus. Take for instance, the maître d’hôtel:

“Andrey was handsome, tall, and graying at the temples, but his most distinguishing feature was not his looks, his height, or his hair. It was his hands. Pale and well manicured, his fingers were half an inch longer than the fingers of most men his height. Had he been a pianist, Andrey could easily have straddled a twelfth. Had he been a puppeteer, he could have performed the sword fight between Macbeth and Macduff as all three witches looked on. But Andrey was neither a pianist nor a puppeteer—or at least not in the traditional sense. He was the captain of the Boyarsky, and one watched in wonder as his hands fulfilled their purpose at every turn.”

— Amor Towles

The Count has the unusual ability to observe small and often overlooked details, such as Andrey’s hands, thus granting the reader an exclusive look into the world as he sees it. Yet, the Count’s character becomes more nuanced as the novel progresses and more about his character is revealed. His past haunts him, while new life and new revelations are revealed. Characters migrate in and out of his life almost arbitrarily, and what appears to be the main plot shifts consistently. The Count learns lessons as the years turn to decades (the novel extends from 1922-1954), as noted in 1954:

“Alexander Rostov was neither scientist nor sage; but at the age of sixty-four he was wise enough to know that life does not proceed by leaps and bounds. It unfolds. At any given moment, it is the manifestation of a thousand transitions. Our facilities wax and wane, our experiences accumulate, and our opinions evolve—if not glacially, then at least gradually.”

— Amor Towles

The events in the Count’s life itself comprise a plot that must be parried with poise, a conundrum to be contemplated. There is beauty in his microcosm of what seems to be a prison, filled with infinite possibilities and endless travelers that come and go through the hotel’s revolving doors. And perhaps, this is how life itself unfolds for all of us. The novel provokes the reader to consider who (or what) occupies their own “Metropol hotel” and how their perceptions and their resulting actions have the potential to affect the world around them, no matter how insignificant the person, their action, or their influence may seem.